What is Privacy Engineering?

05 January 2020

If you’ve heard of Privacy Engineering, you know it is rising rapidly in relevance, but in my opinion, it’s not truly defined yet. It’s 2020, the CCPA is in effect, and with surveillance, IoT, drones, facial and other biometric recognition, cryptocurrencies and increased regulation, it’s going to be a pivotal decade for tech. Early last year, the concept of Privacy Engineering started gathering traction, entering the Gartner glossary, and being pushed by industry groups like the IAPP. It’s an interesting area to understand, because it’s a problem not yet fully solved, and relevant to us all.

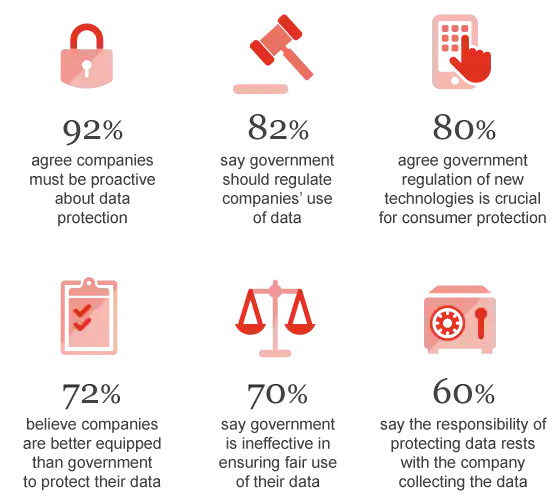

Stats from PWC US’s report on cybersecurity and privacy risks

With the advent of GDPR, the privacy profession has taken off around the world as companies try and bring themselves into compliance, and governments grapple with the privacy issues that modern tech has introduced. It seems like there are two main groups in privacy; lawyers who have chosen to specialize in this area, and a broad range of other organisational professionals who have skilled up in the last couple of years. This is helping companies get policy in line with legislation, and identifying areas of risk, but it leaves a gaping hole. How do you get privacy compliance (aka Privacy by Design) built into your technology? This is important because companies are judged on how they actually use and protect data, so if policy isn’t being enacted in practice, those activities have limited value.

The solution has been labelled as Privacy Engineering. Carnegie Mellon University is pioneering in this space, launching a masters degree, with the intent of creating more privacy engineers.

What does a Privacy Engineer look like?

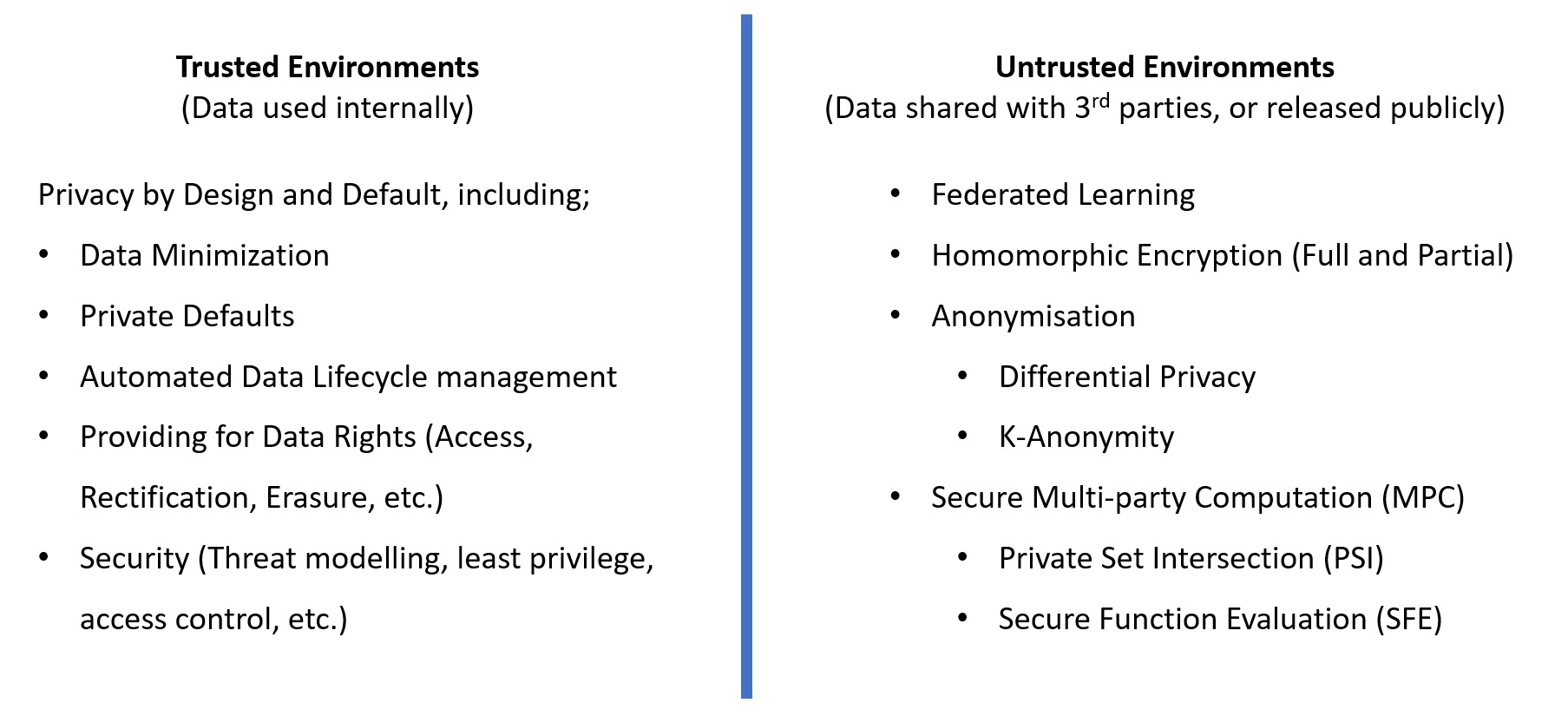

There is a growing need for privacy technologists, but it’s more helpful to think of Privacy Engineering as an activity, rather than a role. A ‘true’ privacy engineer sits at the intersection of too many specializations to be one person; privacy, security, development, data science, and more. Add in the requirements for soft skills and planning, and the result quite rightly looks more like a team than a person. Consider this non-exhaustive list of privacy technologies and techniques:

This doesn’t even encompass understanding privacy law, cloud technology, security or the other hard and soft skills necessary to be effective. It’s for that reason I believe a privacy engineer should be someone with sufficient privacy knowledge and technical literacy to facilitate a team who are domain experts in their own right to build a product or service the right way. With some additional technical literacy, I believe many existing privacy professionals could fill this role.

Hiring for Privacy technology skills

Purely technical privacy roles exist, but they are rare. Google announced last year that it was doubling their number of privacy engineers and other tech giants like Uber and Facebook have similar aims. Since one of the main drivers of Privacy by Design is avoiding fines and legal costs, demonstrating that you are building a system that lawfully processes data is a significant activity. There is a great deal of planning and documentation required from the outset. In the Security field, this process is referred to as Threat Modelling, and privacy professionals achieve a similar outcome with a combination of data flow modelling and Data Privacy Impact Analysis (DPIAs). The difficulty is finding engineers who specialise in privacy-respecting architecture, and it is harder still to find ones who want to document it.

My experience is that privacy skills need to be embedded in the team creating the product or service, and it needs to be done iteratively, with any documentation evolving as the product does. Products and services rarely have a defined end point, so we can’t effectively approach them as if they will remain fixed in one state. It would be ideal to have someone with privacy skills permanently embedded in the team, but it’s more realistic that you will have one person for several teams, and that they lead the privacy function across those teams.

Privacy Ops

It’s not just products and services that need to be designed with privacy in mind, it’s all internal company systems. Like security vulnerabilities, the ideal state is for privacy issues to be discovered and handled through automation and orchestration, which would in turn allow for handling those issues at scale. Data needs to be automatically discovered, classified, and linked to it’s owners. Data retention limits need to self-enforce. Data Subject Access Requests (DSARs) should route to the appropriate people for approval, with identify verification baked in, and should resolve automatically after approval. It sounds unlikely to achieve for something that isn’t a core function for most companies, but this is exactly the gap that a burgeoning industry of regulatory technology vendors seek to fill, and is attracting massive funding to do so.

A small selection of vendors from IAPP’s annual Privacy Tech Vendor Report, 2019

Cloud technologies are already starting to bake privacy functionality in. Data stores like Amazon’s DynamoDB support setting a time to live on data records, so that they expire from your tables automatically. Azure’s Data Catalog automatically aggregates data assets, and advanced threat protection automatically discovers and labels data by sensitivity.

Where to from here?

I don’t think there is a right answer to how this field is going to come together, since it’s still happening in front of us, and I don’t claim expertise in all these fields, but I do believe there are real advantages for those who can make their platforms more trustworthy than their competitors. The question I’d pose to other Privacy professionals watching this field is this; how do you believe the gap between legislation and implementation is going to be addressed?