What *actually* is DevOps?

23 February 2018

DevOps is a pretty popular term right now. It’s well established in many companies and even made it into frameworks like SAFe 4.5. But what actually is it? Most people are aware that it involves automation, but deeper understanding seems to be rare.

Depending on where you stand, you may have different views.

It’s Development and Operations

This is probably the most commonly provided explanation, but it’s also one that doesn’t convey the intent of DevOps. In practice, it’s less about Development joining Ops, and more often about development taking over operations, or operations learning to code. Your people determine your approach, and if you a highly development-oriented team, you are likely to have developed custom solutions, whereas an Ops team who have upskilled are more likely to pull existing building blocks together and script them into repeatable patterns. Both approaches have merits. Everyone needs to learn to code, everyone should be prepared for a call if the system goes down.

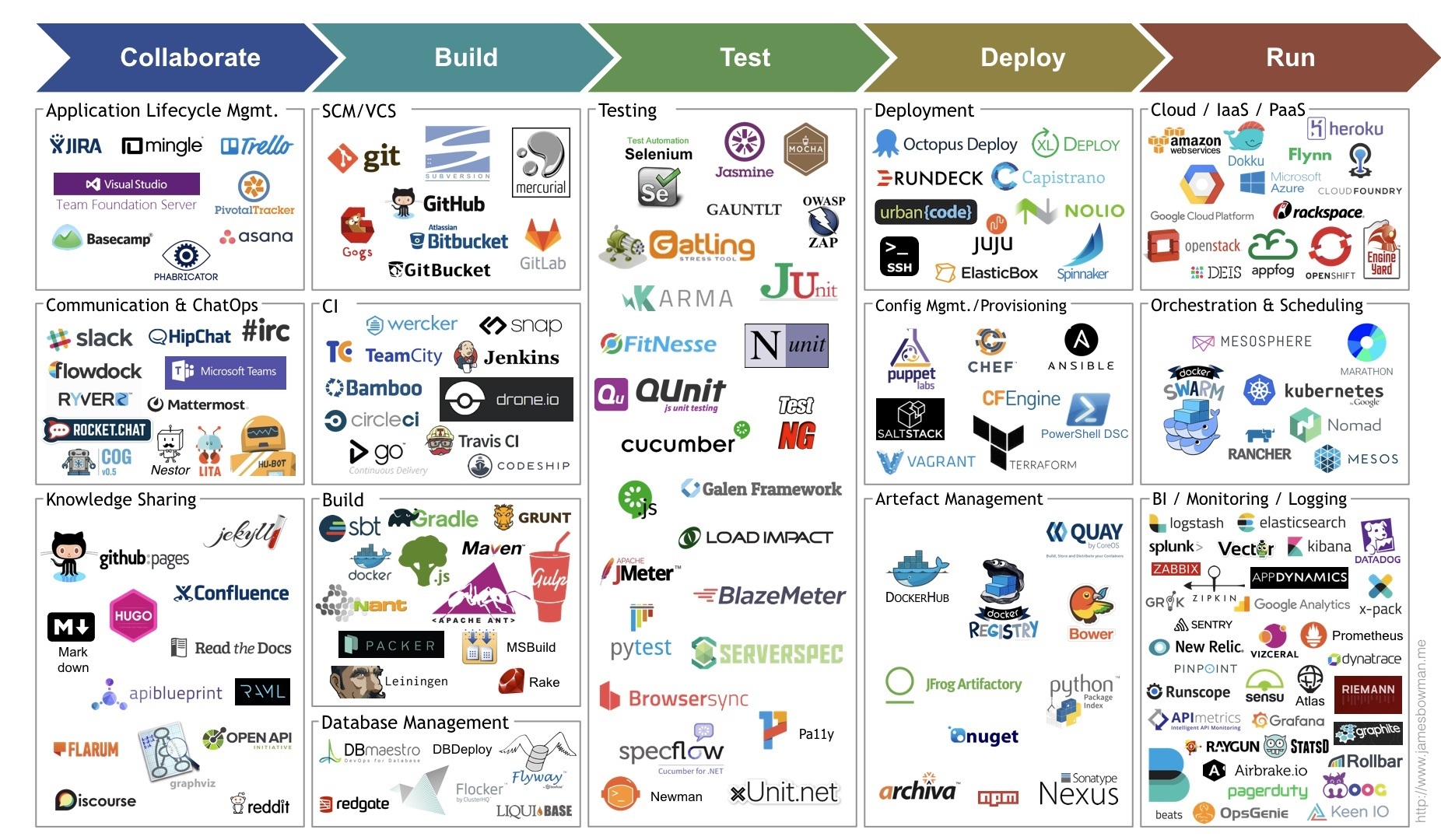

It’s a tool chain

The most concrete manifestation of DevOps in an organisation is an automated pathway to production or at the very least, having systems set up by a group of people who say ‘containers’ a lot. It’s very easy to look at the various mechanisms for orchestrating infrastructure, such as Chef, Ansible and Puppet, container technologies such as Docker and Kubernetes, and say those things are DevOps. But those things are Continuous Deployment; vital to be sure, but not the full picture.

Let’s not discount these though, without these tools, DevOps is not possible.

It’s a methodology

If technologies are the what, the principles of Flow, Feedback and Continuous Learning are the why.

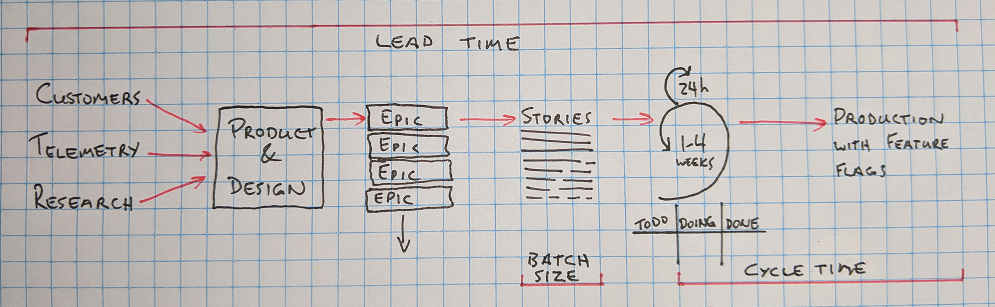

Lean, hailing originally from analysis of manufacturing value streams, teaches us that you first need to make work visible, then you need to limit the number of concurrent activities to expose bottlenecks. These Work In Progress (WIP) limits allow you to identify what is slowing the overall system down, and gives you the free hands to address it. The best leading indicator we have of quality and customer satisfaction is a short cycle time, and this in turn is best predicted by a small batch size. By breaking work down into smaller units and processing them sequentially and fast, we can do better work than attempting five things concurrently.

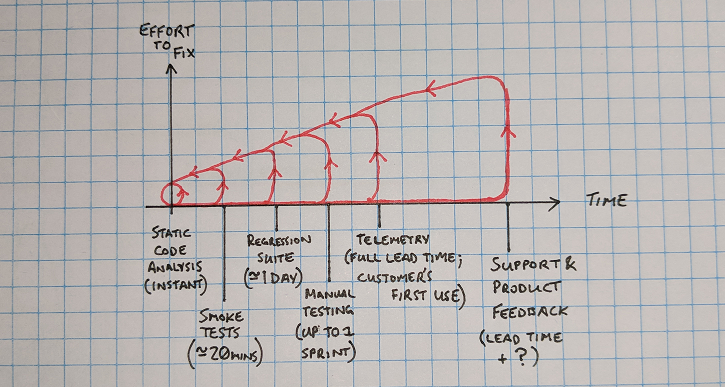

The sooner you learn something is not as it should be, the cheaper it is to fix. Waterfall projects have taught us this the hard way, and agile seeks to address this with iterative development. However, if you can fix an issue before an iteration is complete, you’ll go faster still. Take static code analysis; it’s not going to catch design flaws or incorrect stories but what it does catch will be instant, in the developer’s IDE.

With all these metrics and limits, we will find problems. Problems can be addressed, and the metrics will tell us how well those changes worked. Continuous Learning is core to DevOps, since it exposes many opportunities to work on the overall system. Changing systems can be tricky though; if there isn’t trust in a team, they will wait to be directed. If there isn’t psychological safety, they will optimise for their well-being, not for the system’s. The easiest way to build trust, is to trust, and if there is a failure, address the system, not the people.

So what actually is DevOps?

DevOps is a culture, where work in progress is limited to go fast, feedback loops are created to build knowledge early, and the learning gained is incorporated back into the overall system. It is a culture typified by high-trust, high-safety, and a scientific learning mindset. It is supported by a tool chain of automation technologies, which are in turn enabled by teams with the right training and mindset to optimise them to support the business.

With a summary like that, you can see why it gets shortened to ‘Dev and Ops working together’. But it’s worth doing the whole thing, and doing it properly. Trust me.